Good morning, day or evening to you, dear reader, depending on where you happen to find yourself when reading this. I’m very intrigued to explore today’s subject matter with you, as it is one that has prevailed in our civilisation for quite a while – Vampires.

Blood-sucking, community-terrorising, cattle-killing, immortal and possibly highly seductive creatures of the night, vampires have inspired many a dramatic tale, as well as serious scientific discussion. Now, as it often is the case with these writings of mine, I will surely not be able to delve as deep into this rabbit hole as I would like, at least not in the span of one post, and so I will endeavour to make at least an introduction. I will, as per tradition, do this through the lens of the Czech Republic – the home of McGee’s, as well as a country that happens to have had quite its fair share of vampire presence over the centuries.

As I like to tell guests on our tours, the mystery of the vampire extends far beyond Twilight and Count Dracula, as appealing as those may be, and I tend to think it deserves more than to be discarded as superstition upon first glance.

In Europe, which is where vampire folklore seems to have originated, we in fact have several written records that detail this creature, and they are one of the reasons why I am not so quick to pass the whole thing off as nonsense. So allow me to share some of these for you so that you can make up your own mind.

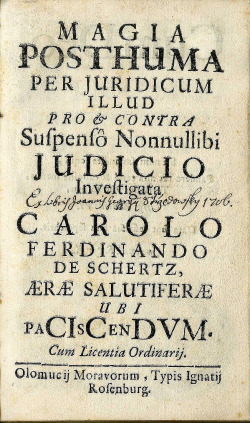

First on the list, we have Magia Posthuma, a book written by Karl Ferdinand von Schertz in 1704 and often turned to for information on the vampire occurrences of the time. It is a very meticulous and scientifically-minded text – von Sherz was an educated man, lawyer by profession, who acted as assessor to the Archbishop of Olomouc, Prince Charles Joseph of Lorraine, and managed his property. He also founded his own village Scherzdorf (present-day Heltinov).

His book details the case of a spectre, in other words revenant, in other words, vampire, that roamed and harmed the living in Moravia. Following the publishing of this book, more of these incidents took place in Moravia and the surrounding regions. Then about two decades later, in northeastern Serbia, Austrian officials also investigated a case where locals referred to a roaming spectre as a vampire. This inspired deacon Michael Ranft to write a study on the mastication of the dead. Eventually, the whole issue got so widespread that Empress Maria Theresa, aided by her court physician Gerard van Swieten, began implementing laws to prohibit the exhumation and destruction of corpses and other ’’acts of superstition’’, as they referred to them.

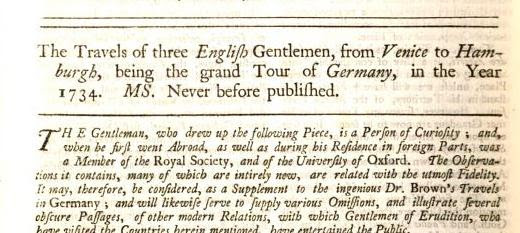

Another source that is often quoted and reached into for information on vampires is The Travels of Three Gentlemen, from Venice to Hamburgh, being the grand Tour of Germany, in the Year 1734, first published in volume IV of The Harleian Miscellany: A Collection of Scarce, Curious, and Entertaining Pamphlets and Tracts, as well in Manuscript as in Print in 1745, and continued in the succeeding volumes. In the manuscript, the authors write that as they travelled through Europe, they encountered again and again locals who told spoke to them of vampirism, and were taking it most seriously:

’’All persons of taste and learning in Carniola have in high esteem the piece of Baron Valvasor, intitled Gloria Ducatus Carniolæ, which, they say, is wrote with the utmost truth, accuracy, and exactness. ’’

The landlord of the three gentlemen, ’’a cheerful agreeable person, and a man of very good sense and understanding, seemed to pay some regard to what Baron Valvasor has related of the Vampyres, said to infest some parts of this country’’

(The Travels of Three Gentlemen, Harleian Miscellany collection, 1745)

Carniola is a historical region of present day Slovenia, one of the countries supposedly most plagued by Vampires, and Johann Weichardt von Valvasor, aka Baron Valvasor, was a natural historian and polymath from Carniola. He was also a fellow of the Royal Society in London – in short, dear reader, by all standards an educated and scientifically-minded man, and he wrote on the topic of vampirism extensively, specifically in the above-referenced body of work Gloria Ducatus Carniolae; The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola, that the locals took so seriously. It was published in 1689, and comprised a total of 15 books (four volumes). That made for over 3000 pages including 528 illustrations and 24 appendices, and concerning our vampirism investigation, dear reader, it also contained the first written document on vampires, detailing the legend of a vampire in Istria named Jure Grando.

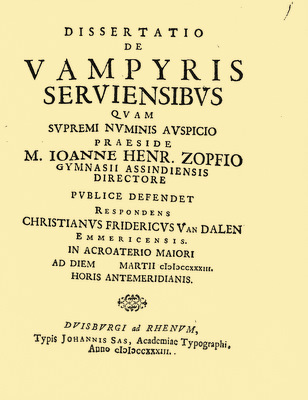

Soon after meeting the landlord who spoke of Baron Valvasor’s works, the three gentlemen also came across a dissertation upon vampires written by the director of the gymnasium in Essen in Germany, M. Jo. Henr. Zopfius, who allegedly wrote:

’’The Vampyres, which come out of the graves in the night-time, rush upon people sleeping in their beds, suck out all their blood, and destroy them. They attack men, women, and children; sparing neither age nor sex. The people, attacked by them, complain of suffocation, and a great interception of spirits; after which, they soon expire.

Some of them, being asked, at the point of death, what is the matter with them, say they suffer in the manner just related from people lately dead, or rather the spectres of those people; upon which, their bodies (from the description given of them, by the sick person,) being dug out of the graves, appear in all parts, as the nostrils, cheeks, breast, mouth, &c. turgid and full of blood. Their countenances are fresh and ruddy; and their nails, as well as hair, very much grown. And, though they have been much longer dead than many other bodies, which are perfectly putrefied, not the least mark of corruption is visible upon them.

Those who are destroyed by them, after their death, become Vampyres; so that, to prevent so spreading an evil, it is found requisite to drive a stake through the dead body, from whence, on this occasion, the blood flows as if the person was alive. Sometimes the body is dug out of the grave, and burnt to ashes; upon which, all disturbances cease. The Hungarians call these spectre Pamgri, and the Servians, Vampyres; but the etymon or reason of these names is not known.’’

(Johann Heinrich Zopf, dissertation on vampires, cca late 17th – early 18th century)

The last sentence of that excerpt, dear reader, nicely carries us over to the next source I feel is pertinent to bring to your attention – a comprehensive and thorough study on the medical phenomena of vampirism, written in 1756 by a German regimental military surgeon Georg Tallar. In said last sentence, M. Jo. Henr. Zopfius touches on the various names given to vampires by the European peoples that were most plagued by them; Pamgri, Vampyres etc.. He leaves out one of the major ones, however, and that is the title of ’’moroi’’, given to vampires by Romanians, which is precisely what Georg Tallar, who served in Romania, refers to them as.

Mr. Tallar served as a physician for over thirty years, and his service to the Habsburg army took him across Romania to places like Transylvania, Wallachia and the Banat. Over that course of time, Mr. Tallar learned the Romanian language well, and thanks to this, he was able to draw on authentic, local sources when conducting his investigation into vampirism – a quality that very few of the studies of the time have.

While working, Tallar was directly privy to five incidents of a vampire attack, and in three cases he was even involved in examining those who were ill, as well as the corpses that were exhumed. What’s more, he had been familiar with a few of the people who ended up turning into moroi.

The victims of the vampire attacks reported to Tallar, and their testimony contained some curious symptoms. First, they said that they had been in bed for a couple of days, and that their heart hurt. Then however, when asked if they could point to where their heart is, they directed to their stomach and intestines. Next they would describe that whenever they tried to fall asleep, the vampire/moroi appeared in the shape of a passed away man or woman, who would stand right in front of them, or in a corner of the room. And almost without fail, they believed that it was necessary to open the graves to look for whom the moroi was, and then thoroughly dispose of the body – commonly, chopping to bits and burning, before scattering the ashes as far as possible, was performed. Mind you, dear reader, the exhuming and destroying of corpses was prohibited by law, but these people were desperate enough that they were willing to break the law to seek out and destroy the moroi. That is how utterly seriously they were convinced of its existence. Many dared not even walk about after dark.

Mr. Tallar also noted in his study that the victims complained from pains and aches in various parts of the body, including strong headaches, and that their tongue would turn pale, then become brownish red, and then dry as wood. They were also very thirsty, and had a faint and erratic pulse.

Upon examining the nutrition of the local Romanians, as well as a series of other factors, Georg Tallar concluded that the ‘vampirism’ was in this particular case a kind of food poisoning and malnutrition, and was able to cure the symptoms in several individuals with an emetic – a medicine that induces vomiting. The story doesn’t quite end there however. Mr. Tallar’s study – Visum-Repertum Anatomico-Chirurgicum, was a part of a larger body of research work – Visum et Repertum, written and attested by various military surgeons in Serbia on 26th January 1732. This collection is one of the most important sources for the history and occurrence of vampirism we have today, and not all of the surgeons that contributed to it were able to so easily rule out the supernatural factor in these incidents.

It would take me far beyond the scope of one article to tell you, dear reader, the entire story of Visum et Repertum, as it is an extensive and fascinating one. Thus, I will endeavour to give you a rundown of sorts.

Most of the military surgeons involved in Visum et Repertum were Habsburg Austrians, stationed in Serbia when it came under Austrian rule. It is there that they dealt with vampirism, and from there they also sent the various reports and correspondences that comprise Visum et Repertum.

It all began with one particular case that was reported to a commander of the Imperial army in Jagodina, colonel-lieutenant Schnezzer, by inhabitants of the Serbian village of Medvedja. They were concerned about a series of mysterious deaths. This was in the fall of 1731. Schnezzer ordered a doctor called Glaser to Medvedja to attend to the issue and examine what had happened. What followed was a year-long investigation eventually involving multiple surgeons, as well as military commanders, local authorities, and even some of the members of the concerned European monarchies.

Doctor Glaser arrived in Medvedja on December 12th 1731 and found no evidence of any epidemic disease, which is what he as a surgeon was accustomed to concluding about the other alleged vampirism cases. We already saw this to an extent with Georg Taller. There were however 13 villagers dead in the past six weeks. To find out what did actually happen now that disease was out of the picture, Glaser opened ten of the victims’ graves and carried out autopsies. To his surprise, while some of the bodies had decomposed as would be expected, others had become bloated and bloody, with fresh blood flowing from the nose and mouth. Upon seeing this, there was no way for Dr. Glaser to ease the villagers’ mind that there wasn’t a vampire running around, and so instead he sent a report to the authorities asking for permission to dispose of the corpses in a way that the local folklore dictated you ought to when dealing with a moroi, granted you don’t want it to keep crawling out of its grave to haunt you.

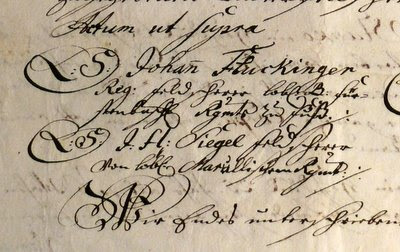

Doctor Glaser sent his report to a commander in Belgrade, who in turn sent a new commission to investigate the matter, apparently finding the Doctor’s findings hard to believe. This commission was led by another regimental surgeon – Johann Flückinger, and arrived in Medvedja on January 7th 1732.

Now, the following months ended up quite the adventure, dear reader. One of the villagers, a man by the name of Arnont Paole, died and supposedly turned into a moroi. By his own admission prior to his death, Mr. Paole said that he was being terrorised by a vampire and took various precautions to kill it, however it seems to have not worked, because the villagers reported to the new commissioner that 20-30 days after Paole’s death, which by the way occurred as a result of a mechanical accident, he was terrorising them as a vampire, and in fact killed four. Thus, the villagers took to exhuming his body and processing it in a way that should end his immortality. Johann Flückinger wrote that when they dug up the body, it was uncorrupted. Fresh blood was flowing from its ears, eyes, mouth and nose, and the clothing and coffin were all bloody. That is when the villagers drove and stake through its heart, which apparently made the corpse groan and bleed intensely, before burning the body and burying the ashes back in the original grave. They observed the same procedure with the four alleged victims of Paole, in case he had turned them into moroi before his end.

Avoid the crowds at Prague Castle with a mystery tour of alchemy and astrology, taking you to magical locations like New World, Strahov Monastery or Prague Loreto.

3 hour tour | from 26 €

Explore hidden places in Old Town and fill your evening with ghost stories and legends full of death, poverty, misery, or murder.

1,5 hour tour | from 16 €

Discover the history of psychiatry and learn about the development of Prague’s famous psychiatric hospital on its vast grounds.

3 hour tour | from 26 €

As if this was not enough to make the events detailed in Visum et Repertum highly concerning, more deaths followed in the next three months. 17 more people died during that period of time, and many of those deaths were permeated by all sorts of horrifying circumstances, such as completely sudden and incredibly severe illness, terror-filled nightmares, fright and various suffocations. In the end, when the flabbergasted Austrian commission exhumed all 17 bodies, they found a majority of them once again uncorrupted, with fresh blood in their body and organs in fine shape. One young woman even died very skinny, and was found fattier upon removal from the coffin. As the officials, somewhat terrified, wrote up the official report, the local gipsies took responsibility for securing the village and yet again observed all the de-vampirising rituals with the undead bodies.

This official report I speak of, dear reader, is the Visum et Repertum, and it includes all of the cases I, believe it or not very briefly, outlined to you just now, as well as many more. It also comprises some other surgeons’ experiences from other parts of central and Eastern Europe, who faced similar mysteries. It arrived in Belgrade first, before being sent to the war council at the court of Vienna shortly before November 1732. What followed was intense public fright and heated scientific debate, much of which, particularly in the case of the latter, goes on till today.

Alright, dear reader! Now that I feel I have sufficiently informed you on the context of vampirism in Europe, let me tell you how our country – the Czech Republic, was affected. As a central European nation, we were most certainly one of the lands plagued by vampires. There were many cases documented by local authorities of settlements, and the folklore is rather rich in blood-suckers as well. Still, that is all somewhat unsubstantial if compared to tangible, archaeological findings that show some evidence of vampirism, and that just so happens to be exactly what was discovered in Čelákovice.

In the year 1966, construction and renovation was being performed on the Vladimír Majakovský street of eastern Čelákovice. As the workers were digging down, they unexpectedly came across what were clearly remains of some kind. This was reported to the local authorities, but seeing as they were clearly too old to be a relevant crime scene, authorities were not interested, and instead archaeologists were called. The following weeks were quite the whirlwind as the archaeologists scrambled to safely excavate and identify the remains before the owner of the construction insisted on resuming, and damaged them to the point of unrecognition. Fortunately for us, they managed, and in the end discovered a total of 11 burial caverns filled with adult remains, dating to cca 11th century. What was incredibly strange however were the features of the buried – they were consistent not with an ordinary burial, but with that of a vampire, specifically designed to prevent them from leaving their graves and murdering innocents.

By the 20th century, historians had quite a good grasp on vampire folklore and culture, and they had classified the steps of vampire burials into two primary groups. The first degree steps, and the second degree steps. Among the first degree steps, and this was seen in Čelákovice as well, the bodies would be laid either on their right or left side, or even their stomach. This was to prevent them seeing the rising sun. Additionally, the limbs, both arms and legs, would be placed in very unnatural and blocked positions, and often tied as well, and the mouth stuffed tightly with various objects. Some of the bodies would also be scorched with fire on the surface, weighed down with stones, driven through with a stake, or even thoroughly nailed down into the ground.

As part of the second degree precautions, the locals would return to the body after some days or weeks had passed, uncover the grave, and sever the head, before moving it separate from the body.

These, dear reader, are the kinds of evidence that led the Čelákovice archaeologists to conclude these people were buried as suspected vampires. There is admittedly also the option of them being criminals, as some of these procedures were observed in the case of serious crime and suicide, but it does not seem so likely. At the very least, as it is with the other cases of vampirism we discussed here today, it is I believe worth considering the possibility that there is more at play here than simply superstition, and that an open conversation on the topic is worth having. Who knows, perhaps there were different kinds of beings roaming the Earth some time ago, which are by nature of today’s world somewhat difficult for us to grasp.

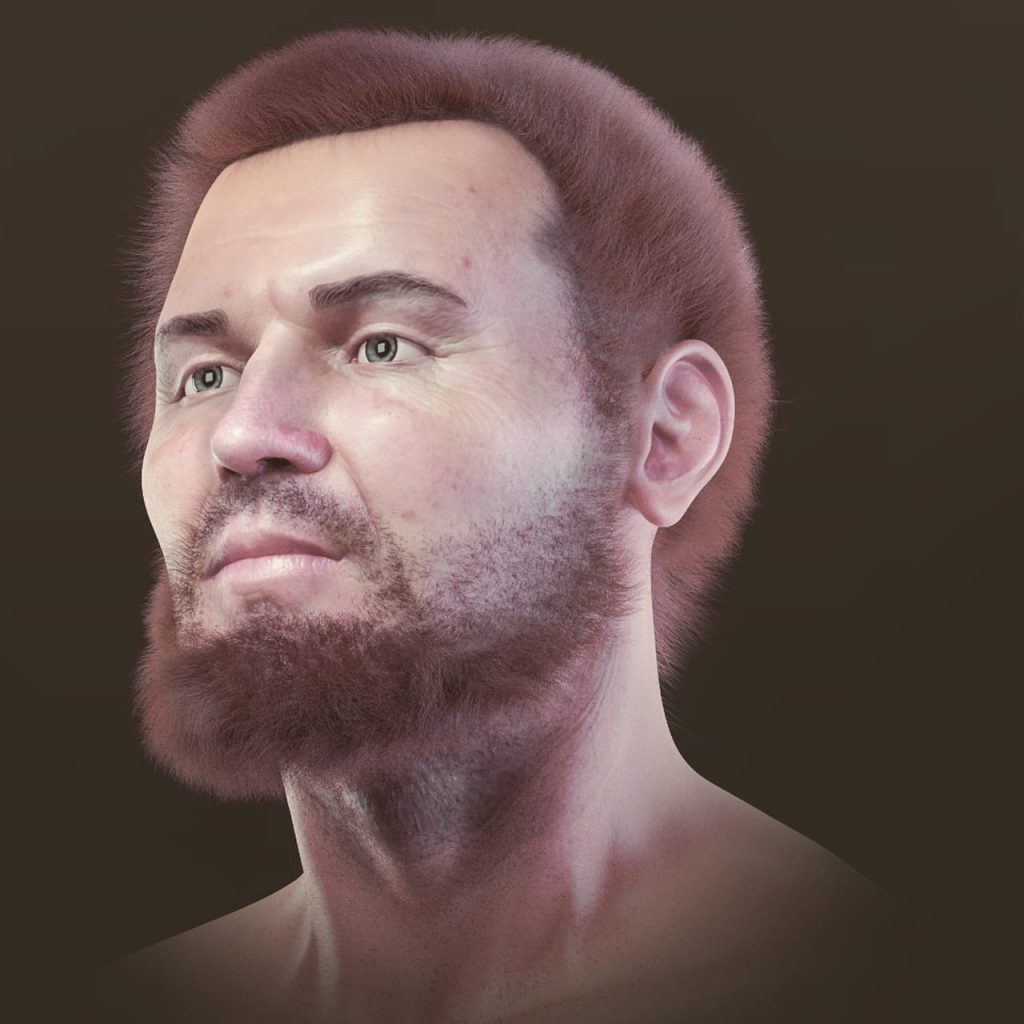

To conclude this article, dear reader, I have a little treat for you. Some years ago, Cicero Moraes, a Brazilian 3D designer and artist, did a facial reconstruction and modelling of one of the Čelákovice vampires. It truly is remarkable how based on the remains found, we now have the chance to imagine in a very life-like way what this person may have looked like, and what their story might’ve been. And thus, dear reader, I will leave you with the image of our Bohemian vampire, and a wish of good fortune till we meet again.

Neli Kozak